Below is an extract about Sir Ernest Fisk from The Australian Dictionary of Biography.

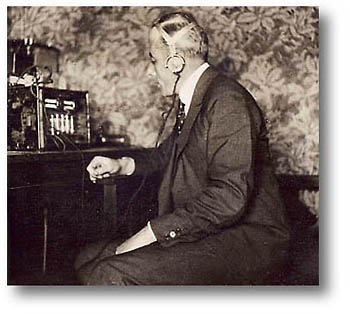

Sir Ernest Fisk

FISK, SIR ERNEST THOMAS (1886-1965), radio pioneer and businessman, was born on 8 August 1886 at Sunbury, Middlesex, England, second child of Thomas Harvey Fisk, builder, and his wife Charlotte Hariette nee Halland He was educated at local schools, St Mary's and Sunbury Boys'. Although he later enrolled at the United Kingdom College, a private London coaching college, and, in 1917, in the diploma course in the department of economics and commerce at the University of Sydney, he sat for no examinations.

From selling newspapers on Sunbury railway station, Fisk 'graduated in engineering' in the works of Frederick Walton, before joining the British Post Office as one of their earliest wireless telegraphists. In June 1906 Fisk joined the Marconi training school. At Liverpool and Chelmsford he learned Morse and wireless telegraphy, qualifying as a radio engineer and operator. From 1909 he worked for American Marconi, demonstrating wireless to the Newfoundland sealers and on the St Lawrence, before returning to Marconi's administrative headquarters in London.

When Fisk first visited Australia in mid1910 in the Otranto to demonstrate Marconi's apparatus for the Orient Steam Navigation Co., wireless was still largely the preserve of amateur enthusiasts. That year the government let the contract for the construction of two land stations for ships to Australasian Wireless Ltd, a Sydney firm with rights to the patents of Marconi's German rival, Telefunken. In 1911 he returned to Australia as resident engineer to represent the interests of the English Marconi's Wireless Telegraph Co. Ltd, trading under several names. His mission was to persuade ship owners to fit Marconi equipment, which he installed and trained telegraphists to operate. He established service depots in Australia and New Zealand. The sinking of the Titanic in 1912 gave business a boost.

In 1912 when the English Marconi Company, sued the Australian government for infringing their patent (and A.W.L. issued writs against firms using Marconi equipment), the government decided in future to use circuits designed by John Balsillie. Eventually the two settled their differences and in July 1913 formed a new company, Amalgamated Wireless (Australasia) Ltd, with exclusive rights throughout Australasia to the patents, 'present and future', of both Marconi and Telefunken. The first chairman was (Sir) Hugh Denison; Fisk, a foundation director, was general and technical manager. In 1916 he became managing director and in 1932 chairman.

At St John's Anglican Church, Gordon, Sydney, Fisk married Florence, second daughter of Samuel Chudleigh, music teacher, on 20 December 1916. Earlier that year, on one of his regular visits to England, he had arranged for a series of test transmissions from the Marconi long wave station in Carnarvon, Wales. With Australia then dependent on underwater cables for its contact with the world, Fisk obtained official permission to use a receiver in his home. In September 1918 he arranged for the transmission of messages to Australia from the prime minister W. M. Hughes [q.v.] and Sir Joseph Cook [q.v.] and established that direct wireless communication between Britain and Australia, was practicable. In August 1919 Sydney received its first public demonstration of radiotelephony.

In 1921 Hughes took Fisk as an adviser to the Imperial Conference in London. Against the recommendation of the Imperial Wireless Committee, which envisaged an Empire linked by short distance relays, Hughes promoted Fisk's scheme for direct communication between Britain and the Dominions. In 1922 the Australian government, insisting that it was not prepared to settle for anything less, commissioned AWA. to create the service, boosted the new company's capital and became its majority shareholder. A beam service between Australia and Britain, undercutting the cable companies, was inaugurated in April 1927; another between Australia and Canada in 1928. In September 1927 A.W.A. pioneered Empire broadcasting; in April 1930 an Empire radiotelephone service. In 1931 Marconi was godfather to Fisk's fourth son David Sarnoff Marconi.

Fisk promoted wireless as integral to the Empire; 'No scientific discovery offers such great possibility for binding together the parts of our far-flung Empire, and for developing its social, commercial and defence welfare'. He became a member of the New South Wales branch of the Royal Empire Society in 1934, and was its president in 1941 and 1944. Awarded King George V's Silver Jubilee Medal in 1935, Fisk was knighted in the Coronation honours of 1937; he went to England for his investiture. In 1933 he had been appointed to the Order of the Crown of Italy.

At the same time Fisk was proudly Australian. He promoted the professional organization of the wireless industry: he was president of the State division of the Wireless Institute of Australia in 1914-22, founding its journal, Sea, Land and Air, and of the Institution of Radio Engineers, Australia, in the 1930s. He was a member of the Institute of Radio Engineers of United States of America, from 1915, a fellow from 1926, and a fellow for life from 1951. In 1923 he had published 'The application and development of wireless in Australia', in the Proceedings of the Pan-Pacific Scientific Congress.

AWA Tower

As head of a major manufacturer, heavily protected after 1920 Fisk promoted the case for local industry and worked to sustain the political, industrial and moral organizations conducive to its prosperity. He contributed to the National Party and its successors. He published 'Ideals in modern business', in Business Lectures for Business Men, no 6, 1933. In the early 1920s he had been a member of the local Royal Society. From 1939 he was president of the Electrical and Radio Development Association; in 1934-36 and 1938-40 vice-president of the New South Wales Chamber of Manufactures, and in 1939-42 a member of the Road Safety Council of New South Wales. A Freemason since early manhood, Fisk was a member of the Electron Chapter founded among A.WA employees in 1937. His favourite recitation at 'smokos' was said to be Kipling's 'If'. He was also a long-time member of the Millions Club in Sydney and the Australian in Melbourne, a member of and in 1939 inaugural chairman of South Wales State Council for Physical Fitness (later National Fitness Council of New South Wales); that year he chaired the Young Men's Christian Association's appeal.

Once knighted, Sir Ernest was asked to join a number of boards. He became an Australian director of the Royal Exchange Assurance of London and a director of York Air Conditioning and Refrigeration Australasia Pty Ltd, Standard Portland Cement Co. Ltd and Sargents Ltd. Another company of which he was chairman, Great Pacific Airways Ltd, formed in 1934 to run an international air service, did not get off the ground. Fisk subsequently used it as a company for private investments. In November 1939 (Sir) Robert Menzies appointed Fisk secretary of the economic cabinet and director of economic co-ordination: the job, of coordination was 'a fantastic assignment', with Fisk by 'background and experience . . . not the man to do it'. In October 1941 (Sir) A. Fadden terminated the position.

While the demands of business meant that Fisk's grasp of electronics was quickly being overtaken, the future he painted for wireless was boundless: lighting lamps, cooking the roast, even driving cars. Wireless raised hopes for an international language and Fisk saw the possibility of communicating with the dead, especially after the death of his son, Thomas Maxwell, on active service in World War II. He showed a continuing interest in spiritualism.

For years Fisk kept a laboratory in his home and had many patents to his credit. Among the best known were, the Fisk solariscope, which distinguished daylight from darkness around the world for users of short-wave radio; and the Fisk soundproof windows which were incorporated into Wireless House, the then tallest building in Sydney which A.W.A. built for its head office at the end of 1939.

By 1944, from 'a cloud no bigger than a man's hand', said Hughes, A.W.A. had grown to cover 'the whole heavens'. With a turnover in excess of £4 million and 6000 employees it had become one of Australia's largest organizations. Fisk that year stepped down to become managing director and chief executive of the Electrical and Musical Industries (His Master's Voice) group in London. In addition to a salary of £10000 plus 1.5 per cent net annual profits (compared with £A4500 plus 2.25 per cent from A.W.A.), Fisk was paid £50000 for the rights to fourteen of his British letters patent. He restructured E.M.I. While profits rose in some areas, including the group's Australian interests, net profits declined in 1949 and 1950 and again after 1951 and he had weakened the firm's long term prospects. In 1952 E.M.I. decided not to renew Fisk's contract: on top of a life pension of £5000 a year, he was retained, nominally, as a consultant for five years at £3000 a year. He returned to Sydney as 'a consultant in commerce, industry and technology', with his business interests now centred on the share market. His views were sought on the future of television, but his main concern was the future of solar, hydro and nuclear power. He still read and while he no longer swam daily, he cycled. The inscription on his coat of arms, mens sana in corpore sano, he rendered as 'fit but not stupid'. He continued to enjoy champagne for lunch and was a member of the Union and Australian clubs, Sydney, and the Royal Sydney Yacht Squadron.

In younger days Fisk declared an interest in landscape garden design: in 1931 A.W.A. had promoted its new works at Ashfield as 'An Australian Factory in an Australian Garden'. He had also been a 'speed demon', establishing 'business driving records' between Sydney, Melbourne and Canberra. In the early 1920s he was a member of the New South Wales section of the Australian Aero Club; and later vice president of the Australian Air League. No longer patron of the Music Teachers' Alliance or the Royal Philharmonic Society of Sydney, Fisk in retirement still enjoyed singing. One of the great entrepreneurs of his time, he was good company and in demand as a speaker. A personal magnetism and feel for public relations earned for A.W.A. and for Fisk himself an enviable press. Even without his high domed head, the Fisk radiola, or A.W.A.'s Victorian establishment, Fiskville, his name in Australia would have been synonymous with the development of radio.

Fisk died at his Roseville home on 8 July 1965 and was cremated with Anglican rites. His wife and three sons survived him. His estate was valued for probate in Sydney at $354,628 and for $11,102 in England; he had settled substantial sums on his children and members of his wife's family after the war. Dr Graham Fisk of Sydney holds a portrait of Fisk.